From Wednesday, August 28th through Wednesday September 4th, our coast was on high alert. Hurricane Dorian roared to within 60 miles of the South Florida coastline, near Martin and Palm Beach Counties.

From Wednesday, August 28th through Wednesday September 4th, our coast was on high alert. Hurricane Dorian roared to within 60 miles of the South Florida coastline, near Martin and Palm Beach Counties.

Early forecasts projected that the storm would crash into Palm Beach with Category 4 strength winds (maximum sustained at 130 to 156 mph). Destruction there would have been close to the catastrophic impact sustained in the Grand Bahamas.

Some forecasts showed a storm track crossing the Florida peninsula to get loose in the Gulf of Mexico. However, once Dorian stalled over the Bahamas, revised forecasts put it on a northern path aimed at Jacksonville. The combined “spaghetti ensembles” using both of the best “models”* closely correlated to a north/northwest track, changing to north/northeast once the upper level steering currents took effect.

Dorian’s stall was unprecedented – historic. Even so, it allowed the storm intensity to wane as it churned up cooler subsurface waters. When the upper level (+18,000 to 20,000’) currents started to coax the storm north, it was downgraded from a Category 5 showcasing a crisp and tight eyewall (over the Bahamas) to a Category 3 with a ragged-edged center and a wobbly track.

Then what happened? Dorian interacted with the Gulf Stream.

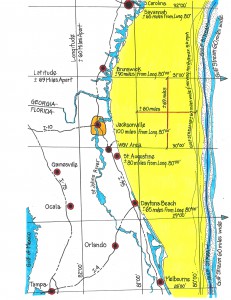

It is important to understand that although the approximately 60 mile wide Gulf Stream contains warm surface and deep waters moving northward at up to 5.6 miles per hour, the Stream itself is not a steering mechanism for a storm.

Dorian’s ragged eye and disturbed center was able to gather over the Gulf Stream and regain its core characteristics as it fed off of the warmer, deep waters. As it continued to gather itself, it began to track along with the Stream, steered by the upper level currents. Note : I learned this from the First Coast News Meteorologist, Tim Deegan.

That dynamic proved to be great news for our area. You can see from the diagram that the western edge of the Gulf Stream is 80 to 100 or more miles east of our coastline. That creates a sort of natural buffer. Additionally, we are further sheltered by being the westernmost community on the eastern seaboard.

Storms that track along the Gulf Stream have their maximum energy fields out to the northeast and east, over the open ocean. Because of this aspect, it is always better to be on the west side of a hurricane, as it moves north.

Sure, storms have a tendency to shift and change their track. In our area, they can plow directly across the Gulf Stream, track between the coast and the Stream, track over or far east of the Stream or interact with the peninsula. That is why the forecasters and meteorologists continually warn about track and “cone” variables**. We would be wise to follow their advice.

In this case, fortunately, the upper level steering together with the gathering over the Gulf Stream enabled Dorian to track fairly true along its northern path to completely clear our “sheltered coast”. It was a great miss.

*The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) primarily use the Global Forecast System (GFS) model. The other more recently dependable model is the European Center for Medium Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF), aka “the European Model”.

**There are many independent, private weather-tracking sources on the web – some of which now require a membership fee. Most all of them import the advisories, data and tracking projections from the National Hurricane Center. The Center posts scheduled updates at 5AM, 11AM, 2PM, 5PM, 8PM and 11PM plus special advisories whenever conditions merit. Ever since I attended a National Hurricane Conference in 1979, I have checked the National Hurricane Center as the best go-to source for dependable storm information – www.nhc.noaa.gov – or just Google National Hurricane Center.

Here’s another Advisory: if you want to learn more about the history of storm tracking and immerse yourself in hurricane lore – please read, Isaac’s Storm ; A Man, a Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History, by Erik Larson – about the September 1900 Galveston, Texas storm.